Close to half of the babies that are born using advanced fertility methods are part of multiple births—twins, triplets, etc.—according to emerging federal figures. While large multiple births have dropped, likely following the notorious “Octomom” case, writes The Associated Press (AP), twin births continue to occur at the same rate. At issue, according to fertility […]

Close to half of the babies that are born using advanced fertility methods are part of multiple births—twins, triplets, etc.—according to emerging federal figures.

Close to half of the babies that are born using advanced fertility methods are part of multiple births—twins, triplets, etc.—according to emerging federal figures.

While large multiple births have dropped, likely following the notorious “Octomom” case, writes The Associated Press (AP), twin births continue to occur at the same rate. At issue, according to fertility specialists, is that twins have increased risks for significant health problems, including higher risks for premature births.

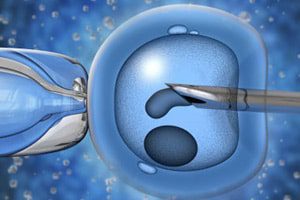

Today, fertility experts are urging for one-embryo babies and more and more couples are trying to get pregnant with just a single embryo, according to the AP. It seems that there are ways, today, to choose those embryos that will successfully be brought to a full-term birth. Emerging guidelines are seeking to have physicians focus on this option.

Many patients “are telling their physicians ‘I want twins,'” said Barbara Collura, president of Resolve, a support and advocacy group, the AP reported. “We, as a society, think twins are healthy and always come out great. There’s very little reality” about increased medical risks for twins and their mothers, she noted. While some couples prefer the one-embryo approach, others prefer to enter into vitro fertilization (IVF) with no less than two embryos due to financial concerns and in the hopes that the multiple embryos will increase their odds of at least one healthy birth. Having two babies at one time is more cost effective many of these prospective parents feel, as well, according to the AP report.

New data released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reveals that 46 percent of IVF babies are multiple births, typically twin births. Of these, 37 percent are born premature, compared to just 3 percent of the babies who are born with no fertility help who are twins and about 12 percent born pre-term, according to the AP.

The issue appears to be unique to the U.S.; some countries in Europe that pay for fertility treatments require the use of just one embryo per attempt. Now, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) seeks to make that limit the norm in the U.S., as well. The updated guidelines indicate that, in women who are under the age of 35 and who are believed to have a reasonable likelihood of success, the single embryo transfer should be offered. These women should not be permitted to exceed two embryos at a time. Because the trouble with conceiving increases with age, the number of acceptable embryos will increase with a woman’s age—two-three embryos for women up to the age of 40, the AP wrote.

The guidelines also say that counseling on the risks of multiple births and embryo transfers should occur and should be noted in medical records. “In 2014, our goal is really to minimize twins,” said Dr. Alan Copperman, medical director of Manhattan fertility clinic, Reproductive Medicine Associates of New York. “This year I’m talking about two versus one. Several years ago I was talking about three versus two” embryos, he added, according to the AP.

According to Lawrence Engmann, MD, at the Center for Advanced Reproductive Services at UCONN, “the delivery of a healthy single baby is the ultimate goal after IVF treatment and … the elective transfer of a single embryo ensures that this goal can be achieved.” Dr. Engmann notes that studies reveal that prospective parents seek twin births over the “coolness” factor, the cost efficacy of going through multiple births at one time, and the convenience of completing one’s family after one attempt. The truth is, notes Dr. Engmann, that multiple pregnancies are tied to serious maternal and perinatal complications,” not to mention the “financial burden to the individual and the health service.”

Complications to the mother include increased risk of miscarriage, high blood pressure, diabetes, and early delivery; risk of cesarean section; and increased risks for psychological and social problems. Babies are at significant risk of being born early—43 percent for twins and 92 percent for triplets, compared to 9 percent for singles births and a 25 percent increased risk for life-long disability in babies born very prematurely, according to Dr. Engmann.

Even more alarming, notes Dr. Engmann, is the risk of death by the first year of life. This risk is increased to seven-fold in twins and 20-fold in triplets. Cerebral palsy is four times more prevalent in twins and 17-times more prevalent in triplets. As for cost-efficacy, longer term twin birth costs are far greater than any savings from avoiding multiple IVF cycles with single embryo transfers, says Dr. Engmann.