A jury just awarded more than $5 million in damages to Cow Island, Louisiana, residents over arsenic-contaminated soil and groundwater tied to a cattle dipping vat. The award is for various cleanup of the water and soil near the vat. The lawsuit began with a Cow Island priest’s cancer fight, according to TheInd.com. That priest […]

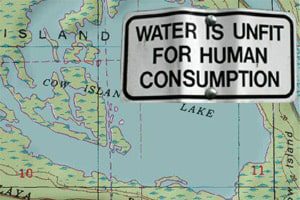

A jury just awarded more than $5 million in damages to Cow Island, Louisiana, residents over arsenic-contaminated soil and groundwater tied to a cattle dipping vat.

A jury just awarded more than $5 million in damages to Cow Island, Louisiana, residents over arsenic-contaminated soil and groundwater tied to a cattle dipping vat.

The award is for various cleanup of the water and soil near the vat. The lawsuit began with a Cow Island priest’s cancer fight, according to TheInd.com. That priest was the second of two diagnosed with cancer at the Cow Island rectory. The priest had his water tested in 2004 and found that the water contained very high levels of arsenic. He suggested his parishioners also have their water wells tested.

Cow Island residents learned that their wells were contaminated with arsenic in very high amounts. The maximum allowable limit for drinking water is 10 parts per billion (ppb), which, although allowable, is still high, noted the attorney involved in the matter. Meanwhile, some Cow Island water wells’ tested from 20 ppb to a very serious 800 ppb of arsenic, according to TheInd.com; most wells tested between 40-60 ppm. According to the attorney, if a public water system tests with 11 ppm, that system would be shut down.

Engineers were hired and found an old community cattle dipping vat to be to blame. The parish bought the vat at the turn of the 20th century as part of the government’s Tick Eradication Program in place from the early 1900s to 1937 over Texas Tick Fever, according to TheInd.com. William F. Cooper and Nephews, the world’s largest manufacturer of arcynical dip for most of the 20th century, produced the dip, which was widely used long after the program ended.

At the time, the approved method of disposing of the dip was to simply pour it on the ground. The company advertised this as a safe disposal method, never disclosing the poisonous nature of arcynical dip and that the poison could seep into groundwater, according to TheInd.com. The dip was used On Cow Island up until the 1970s and, when the residents discovered the source of the contamination in 2004, Cooper’s was long gone. Arcynical dip was banned by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1975.

Cooper’s appears to have intentionally deeply hidden itself in a serious of acquisitions that ended with drug maker GlaxoSmithKline.

The verdict puts $746,120 of the $5.1 million awarded in a trust for contaminated water and soil cleanup near the old dipping vat. The other $4.3 million is for a special court-administered fund for groundwater cleanup by the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality. The initial verdict, noted TheInd.com, is for just one of four contaminated areas in Vermilion Parish that are part of the litigation.

Arsenic can be toxic and carcinogenic and ongoing arsenic exposure can, at first, lead to gastrointestinal problems and skin discoloration or lesions. Long-term exposure—described by the World Health Organization (WHO) as between five to 20 years—could increase risks for cancers, high blood pressure, diabetes, and reproductive problems.

Arsenic can be found naturally in water, air, food, and soil in both organic and inorganic forms. While organic arsenic passes out of the body quickly and is considered harmless, inorganic arsenic, which can be found in pesticides, for instance, and which was found in the cattle dip, can be toxic and carcinogenic.

Acute or immediate symptoms of a toxic arsenic levels, according to MedicineNet, may include: